That’s the question posed by James Breckwoldt in a fascinating study that uses Simpsons characters as archetypes to analyse changes in US society. This is not a matter of judging right or wrong, left or right. It’s a useful framework for understanding political realignment.

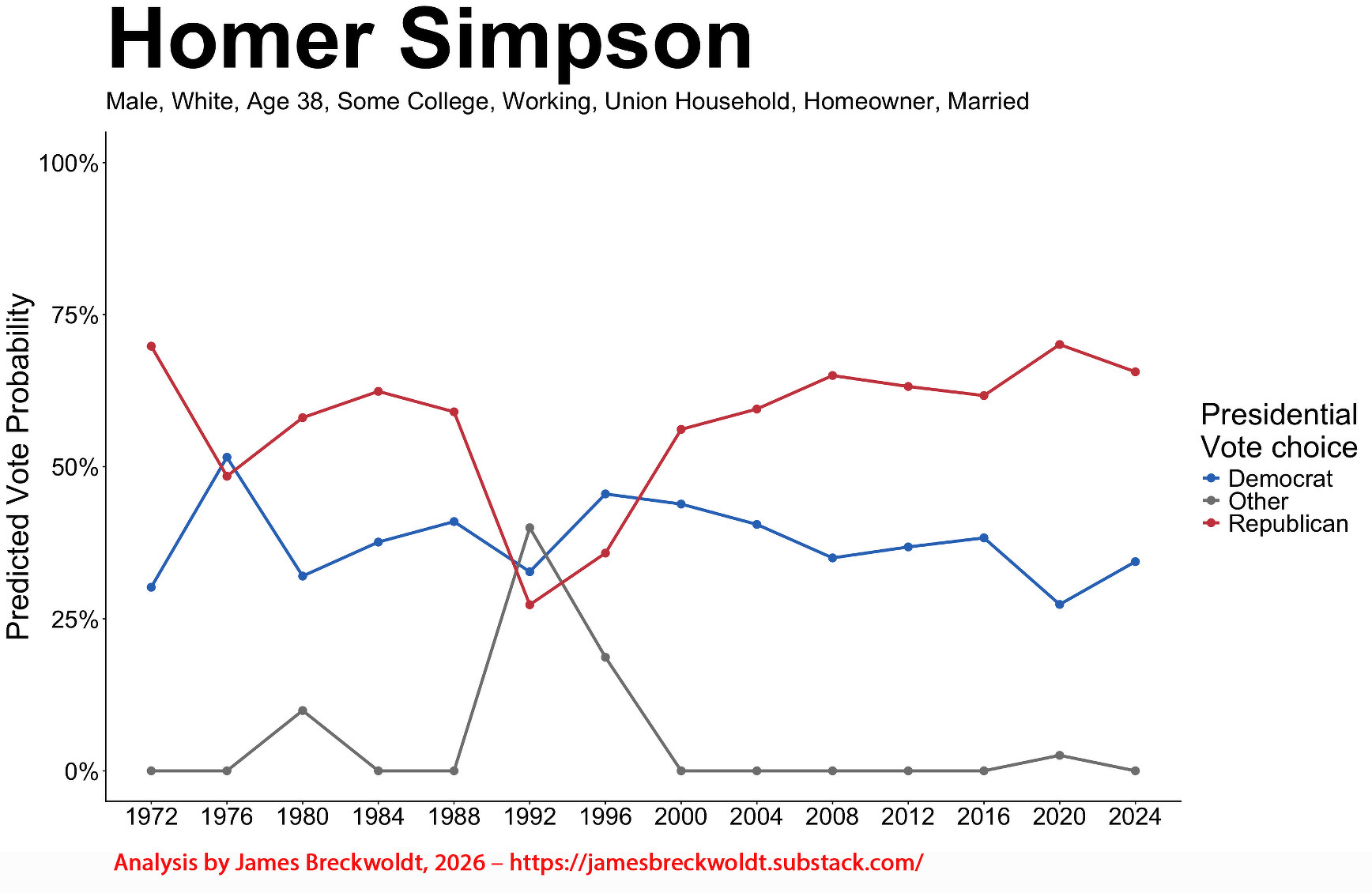

Breckwoldt uses American National Election Studies (ANES) data to model how characters from The Simpsons would have voted in every US presidential election since 1972. The Simpsons have been running for 36 years now. A lot has changed in that time.

Homer Simpson, that archetypal working-class union member from Springfield, would have been a solid Democrat in the show’s early ’90s heyday. But today? His demographic profile places him squarely in the Trump camp.

Meanwhile, Mr Burns, the plutocratic nuclear plant owner who literally blocks out the sun to increase energy consumption, now aligns with the Democratic Party’s demographic base. Not because Burns developed a progressive conscience, but because cultural presentation and elite social status have become more politically significant than raw economic interests.

The billionaire and the working man have swapped teams. Neither switch has much to do with their actual material interests.

Why this matters

What makes Breckwoldt’s analysis compelling is how it illuminates the cultural-versus-economic fault lines in modern politics.

For wealthy voters like our hypothetical Mr Burns, Trump’s manner (described as “uncouth, loud, unpolished”) threatens something more valuable than tax policy: social status within elite circles.

And for Homer? The shift works in reverse. The union card that once signalled Democratic solidarity now sits awkwardly beside a cultural alienation from urban progressivism. Homer’s scepticism of fancy-talking elites, his blue-collar identity and his distance from the concerns dominating educated coastal conversations all push him towards a party that once represented everything his union fought against. The economics haven’t changed, but the cultural signalling has.

Breckwoldt steps through all the main Simpson characters and uses them to explore changing demographics and voter trends. I found it fascinating.

This isn’t about cartoon characters. It’s about how political tribes are increasingly sorted by cultural signifiers rather than economic platforms.

Where I found this

I discovered Breckwoldt’s piece via James Marriott’s Cultural Capital newsletter.

James Marriott is a columnist and writer at The Times (London), where he previously served as deputy literary editor on the paper’s books desk. He’s the voice behind Cultural Capital, a weekly Substack newsletter that’s built a following of over 37,000 subscribers by tackling everything from the evolutionary psychology of religion to the poetry of John Donne to the worldwide decline in literacy.

Cultural Capital lands once a week and consistently delivers high-quality curation. Marriott doesn’t just link-dump. He finds smart takes hiding in corners of the internet you might not frequent and presents them with context that makes you reconsider your assumptions.

If you’re interested in how culture shapes politics and our world, it’s worth adding to your email subscription list.

Read James Marriott’s latest issue of Cultural Capital.

Credit to James Breckwoldt for the original analysis and James Marriott for surfacing it.